Duane Mayes grew to love helping others at an early age. He and his two siblings were born and raised by deaf parents. His father also had physical disabilities from polio. Although he and his siblings are not hearing impaired, American Sign Language is their first language and was the primary language in their home.

Mayes was an active volunteer in high school, helping students with disabilities. He began his career in social services right after high school when he worked as a certified nursing assistant in a nursing home.

Now, as director for the Alaska Division of Vocational Rehabilitation Services, he has 40 years of VR experience, including in the private and public sectors, with special education councils, veteran’s administrations, workers compensation, senior and disabilities services, and health and social services. He has been a rehabilitation counselor for the deaf and served as an adjunct professor at the University of Alaska-Anchorage, teaching beginning and advanced ASL.

With a wealth of experience and rich stories to share, the UW-Stout alum recently was a keynote speaker at the Stout Vocational Rehabilitation Institute’s first Innovation Inspiration Expo, which drew in VR professionals from every state.

In a broad sense, the expo stemmed from the federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, which funds workforce development and job centers through the 78 VR state agencies across the country, represented by the Council of State Administrators of Vocational Rehabilitation.

Through the act, CSAVR and agencies are charged with finding new ways to serve clients by coordinating workforce development and related programs.

“The expo provided a platform for frontline vocational rehabilitation professionals to share innovative and creative ideas with colleagues across the country to improve the consumer VR experience,” said SVRI Executive Director Kyle Walker.

The virtual three-day expo, held Jan. 24-26, featured keynote presentations and 27 prerecorded presentations, followed by live discussions.

Presenters included the Virginia Department for the Blind and Vision Impaired, which shared how it developed accessible STEM curriculums in public schools. Other presentations ranged from innovations in government, small business services, accessible online portals for clients and program resiliency through the pandemic.

“It is easy to get into the rut of maintaining the status quo without consideration of what and how other state programs may be doing the same work with new and innovative practices,” one attendee commented. “This forum allows the opportunity to learn from multiple entities and various perspectives.”

Mayes’ presentation, “Past, Present and Future of Vocational Rehabilitation,” asked attendees to remember what shaped them, what has worked well for them and their clients, and what must be done to align VR with the future.

Evolving to be a leader in vocational rehabilitation

Mayes explained how he evolved to be a leader, rewriting policies and creating new programs and services. He sees the relationships he’s built as the most important aspect of his career and understands that finding solutions in VR involves ongoing communication with agency partners and clients. He encourages professionals to get out of their offices and engage with employers in the community.

And he emphasized the importance of listening to others and the power of sharing stories, including his family’s and his VR journey.

Mayes’ insight and awareness of disabilities began at a young age, at home with his parents, and he felt blessed to be able to understand their experiences. “My parents were instrumental in where I’m at today,” he said.

His parents grew up on farms – Betty in central Wisconsin and Gerald near Omaha, Neb. Betty left school in sixth grade because of a lack of accommodations for her deafness. Gerald attended Omaha School for the Deaf, where he felt he thrived in a supportive community.

Gerald and Betty eventually settled in Wisconsin to raise their family. When Gerald felt discriminated against by his employer in his position as a press machine operator for a local newspaper, the family moved to New Holstein, where he found a similar job.

There, Betty worked on an assembly line at a local factory for 35 years, but Gerald felt discriminated against and quit his job. After eight years working for the local paper, he received no pay raise when he knew his co-workers were receiving raises. He had difficulty finding new employment.

The family was unaware of any vocational rehabilitation agencies in the area. So, at the age of 12, Mayes helped his father navigate the complexities of the workforce hiring process, assisting him in his job search. This was Mayes’ first experience in VR, although he didn’t realize it at the time.

Mayes and his siblings attended job interviews with their father to translate sign language for him. They often heard employers remark that they wouldn’t hire a deaf man, even before the family had left the office.

“Our memories of discrimination against our dad in this time are crystal clear,” Mayes said.

Eventually, Mayes called his mother’s manager at the factory, whom he felt respected his mother, and asked him if he would meet with his father. Gerald was hired on the spot.

“It’s all about who you know,” Mayes said.

Living in a household with ASL as the primary language, Mayes worked with a speech therapist as a young boy to learn English. In high school, a special education teacher who lived across the street took him under her wing and invited him to volunteer in her classroom.

“I’m thankful to them for helping me evolve to who I am today,” he said.

After high school, Mayes held several jobs, including as a certified nursing assistant. He was a roofer for a local construction company, drove tractor and picked oranges in Florida. But he needed direction.

His brother, Bill, was attending UW-Stout for his bachelor’s in vocational rehabilitation, now rehabilitation services, and encouraged Mayes to apply. Their sister, Bonnie, later attended as well.

“My brother was influential in my going to Stout, connecting me with staff and students,” he said. “I felt an absolute sense of purpose.”

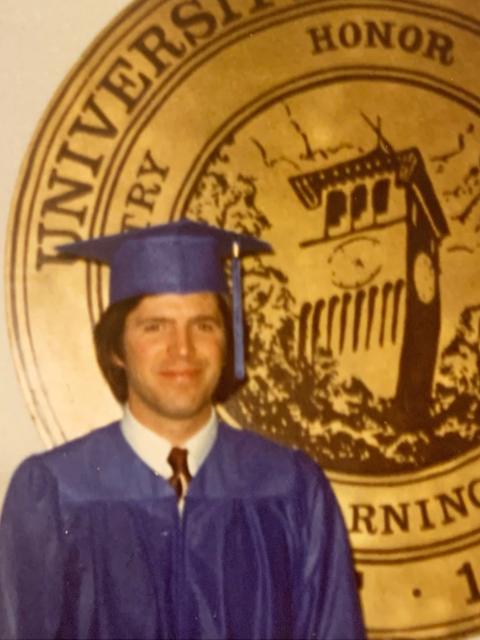

Mayes believes the university changed the dynamics of his family’s life and significantly transformed his professional life and the lives of his siblings. All three have their bachelor’s in vocational rehabilitation from UW-Stout, and Mayes and his sister have their master’s in vocational rehabilitation from UW-Stout, Mayes receiving his in 1982.

So began the next chapter of Mayes’ VR journey and his road to Alaska. His mentor at UW-Stout, Professor John See, encouraged him to follow a job lead he’d heard about. Mayes took his very first flight to Alaska and interviewed with Roger Weed at Collins, Weed and Associates, as a private rehabilitation counselor in worker’s compensation.

The private rehabilitation company, however, would not hire Mayes because he had no professional experience. He returned for a second interview and was denied the job again. Mayes was relentless. He returned to meet with Weed a third time, and when Weed would not speak with him, Mayes sat in the office waiting room for hours until he could speak to him once more.

“I told Roger, ‘I can guarantee you I’m the person you want for this job,’” Mayes said, because although he didn’t have professional experience within a VR agency, he believed that helping his parents, volunteering in the special education classroom, his education at UW-Stout and his drive to help people were enough.

Weed gave him a chance. Mayes flew home to Wisconsin. He and his wife, Macrina Fazio – also a vocational rehabilitation specialist – packed their belongings and drove nonstop to Alaska four days later.

“It’s the same when I’m talking with consumers,” Mayes explained. “When you’re looking to reach a goal, how bad do you want it? What are you willing to do?”

When Betty retired in 1991, Mayes flew home from Alaska to act as her ASL interpreter at her retirement party, as there was no one at the factory who signed. Her managers and co-workers didn’t understand why Mayes volunteered to do this because they thought Betty could hear them well enough.

As she signed her farewell speech, Mayes translated for his mother. She thanked them for their kindness, but she needed them to know that when they talked to her, she would often just smile and nod. Although she felt grateful for her job and the friendships she made, she couldn’t hear them.

Betty’s manager and co-workers were surprised by her words, as her son voiced her truth. After working with her for 35 years, they discovered they truly didn’t understand her deafness.

Gerald retired the same year and was then involved in a pedestrian accident that left him with two broken legs and a broken shoulder. He spent six months recovering in a nursing home. When he was able to return home again, Mayes flew back to modify his parent’s home and vehicle.

“Having a background in VR made a difference. I could apply my UW-Stout education to help my parents so they could live as independently as possible within their home,” Mayes said.

Much of his identity comes from his parents driving him to be the best he can be, he said. “So, why do I do all of this?” he asked toward the end of his presentation, reflecting on all he’s done in his VR career.

“Because my parents are watching,” was his simple, heartfelt answer.

An expo for frontline professionals

Stout Vocational Rehabilitation Institute provides solutions to impact the future of people with disabilities through services, research and education programs for VR professionals. It serves to advance programs and practices in disability and employment.

Walker and SVRI Director of Education Terry Donovan believe some of the most innovative and creative solutions come from frontline professionals who work directly with clients. However, Walker, who has been in the profession for more than 20 years, has never seen a platform for professionals to present to other professionals.

In developing the Innovation Inspiration Expo, it was key for frontline professionals to be able to attend. The virtual aspect cut travel expenses and enabled agencies to register more staff.

At other VR conferences, most attendees are administrators and directors, Donovan noted. “At Innovation Inspiration, 90% of the 348 attendees were frontline professionals, from all 50 states and national territories, meeting our goal of creating accessible material for all VR professionals,” he said.

“Having the prerecorded material was also unique,” Walker added. “Most conferences offer presenters and breakout sessions, and you just can’t get to them all. With the prerecordings, attendees can see everything, and it’s all on their schedule.”

The presentations were available to registrants for an additional two-week window. SVRI provided 29 continuing education units for certified rehabilitation counselors.

“We truly had a national-scope conference, all managed in little old Menomonie. Stout is on the cutting edge of VR training and evaluation. Innovation Inspiration allowed us to add to that brand, where Stout is the VR place – and future place of VR,” Walker said.

SVRI was formed in 1966 through Department of Health, Education and Welfare grants. Located in the Vocational Rehabilitation building on campus, it generates more than $4 million dollars annually through grants, contracts, and other federal, state and local partnerships.